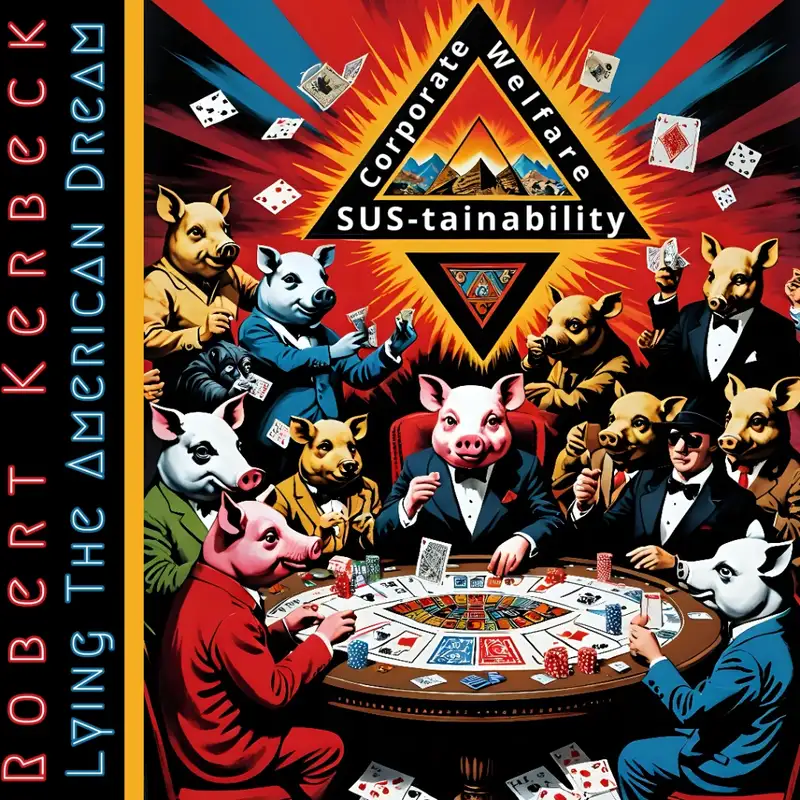

Robert Kerbeck - Lying, The American Dream

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome back to the true life podcast. I hope everybody is having a beautiful day. I hope the sun is shining. I hope that the birds are singing and I hope that the wind is at your back. Got a great show for you guys today. Let me just pose this question to everybody within the sound of my voice. What happens when an aspiring actor trades the bright lights of Hollywood for the shadowy underworld of corporate espionage? Meet Robert Kerbeck, a man who has lived two extraordinary lives, one on stage and one in the high stakes world of deception. Robert's gripping memoir, Ruse, lying the american dream from hollywood to wall street published by penguin random house is a true crime thriller that takes you behind the scenes of america's most powerful corporations in ruse robert reveals how he became the world's greatest corporate spy using social engineering or rusing to infiltrate the very heart of corporate power even frank abgnale the legendary con artist of catch me if you can praises robert for elevating the art of the con to new heights while Sean Delan Hale's ruse as a story almost too good to be true. From mingling with Hollywood elites to working with OJ Simpson just weeks before his infamous car chase, Robert's life is a whirlwind of ambition, deception, and reinvention. Today, we dive into the mind of the man who's lived on both sides of the American dream, from the glitz of Hollywood to the hidden world of corporate espionage. Robert Kerbeck's story will leave you questioning the thin line between truth and lies, ambition, and morality. This conversation is gonna be fun. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome back to the True Life Podcast. Robert, how are you today? Well, I'm doing great, especially after that lovely introduction. Thank you, my goodness. Well, the pleasure is all mine. You got a brand new book out and you've lived an incredible life. And in that life, you've gained some really incredible life experience, man. I want to get into it today, but I thought I'd maybe let you paint a little bit more background. How are you now? Maybe you could flesh out the background a little bit more on how you got to be where you are today. Well, I think to do that, you got to go back to the beginning, right? And my hometown is Philadelphia. great grandfather sold horse carriages before automobiles were invented and he saw the writing on the wall and he switched and became one of the first car dealers in philadelphia my grandfather took over that dealership my father took over that dealership and I was supposed to take over that dealership but of course I fell in love with acting when I was in college And my father was very disappointed in me, especially when I moved to New York to pursue acting. And of course, actors need survival jobs. And I wasn't I was a terrible waiter. I tried it. I was an even worse bartender. And eventually I needed a job. I only had one friend in New York. And He mentioned this job one day and then he shut up right away. Like he'd been told, don't talk about this. Don't tell anybody about this. And I said, whoa, dude, I'm broke. I need a job, help me out. And so he very reluctantly got me an interview. And it was with this woman that had this small corporate spying firm, which of course I didn't know at the time. And I go to her place to do an interview. She's got a doorman building, Upper East Side. I'm living in a small cave in Hell's Kitchen. And so right away when I got to the building and I went up to the penthouse, I knew whatever she was doing, it was lucrative. And then she opened her apartment and it was the nicest apartment I'd ever been into. I mean, apartment doesn't even do it justice. um and so I knew whatever she was doing she was making a ton of money and I have a very strange interview she never asked me any questions about myself she never tells me a thing about the job sends me on my way I figure I blew it my buddy calls and he says you got the job but don't get too excited because no one is able to do this job and the very next day I got sent out to um brooklyn to the home or the apartment of this woman who was the trainer for the woman that ran the corporate spying firm and that was when I began to learn that what we've been hired to do was infiltrate corporations and get people to tell us things that they should never in a million years tell us Man, it's so closely tied to the foundation of a Hollywood movie, man. And I could see how those two things are related. At that point in time, were you just blown? You're like, wait a minute, I'm going to do what? What was the relationship? What was going on in your mind? Were you like, oh, this is kind of like acting? What was going on in your mind at that point in time? Great question. You know, so when I when I first get to this woman's apartment, first of all, I walk into the apartment in Brooklyn and there's a bathtub in the living room. And the woman who was quite attractive says, come on in, you'll work in my bedroom. And. I had no idea what the job was. I was single though. So I was like, well, okay, let's see where this is going to go. And so I go into her bedroom and there are only two pieces of furniture in the room, a futon on the ground and a desk. And she says, sit down at the desk. And she begins to tell me what we do. And then of course I'm, I'm very confused. And so she picks up the phone and makes a phone call to a major wall street firm. And she puts on an Irish accent. And she concocts this whole crazy story, which seemed ludicrous to me. And yet she got the assistant of a major executive to release all of this private information to her, which then she in turn gave to the woman who ran the firm, who then sells that information to that company's rival. Wow. When I heard her do this phone call, you know, one of the things about corporate spying is, you know, we all know the Russians buy on the Chinese, the Chinese buy on us. But what most people have no idea is that. And somebody asked me that the other day. They say, you know, Robert, do most companies in America hire spies? I said, no, most companies don't. All companies do. All companies in America globally hire spies. Now, they're not going to tell you that. They're not going to advertise that. And of course, they do it. They hire intermediary firms because they don't want to get in trouble. They don't want to get caught. So if Robert gets caught spying, they can say, well, we didn't hire Robert. This consulting firm hired Robert or this executive recruiting firm hired Robert. We have no idea. But I'm here to tell you that I have over the years presented my extracted data. I've personally presented it to individuals that today are the CEOs of some of the largest companies in the world. That sounds dangerous to me. It sounds like that information could be so not only the rivals, but like corporate security fraud and lawyers and attorneys, man. Like that sounds like a pretty dicey situation to be into, man. Yeah. So after the first phone call, this attractive woman puts on an Irish accent. Are you like, whoa, this girl is pretty talented or like, what were you thinking? Like I could do this or like, I can't do this. What was going through your mind then? Well, and that's a great question. Cause I think there was as much as I was like, whoa, this is, this is a little questionable. There was also a part of me as the actor going, well, you know, I could do I could do an accent, you know, maybe maybe my Irish won't be as good as hers. But this is Manfred calling from the office in Germany. You have the European Union regulators here. We need some information from the States. Yeah. I'm like, I could do some accents. And so there was part of it that was challenging as a young actor. And by the way, when we started doing this job, we were getting eight dollars an hour, eight dollars an hour, which is hilarious because for your listeners out there, I took that eight dollar an hour job and by the end was making two million dollars a year as a corporate spy. Do you remember your first gig? My first buying gig? Yeah. We were, this is insane. We were hired to infiltrate defense companies and get people that were handling top secret weapons programs and get information about those firms, those programs, who was in charge of them, what they did. Now what's insane was we were getting that information to sell to companies their rivals, which was another American defense contracting firm, right? But if I'd been hired to do that and get that information for Russia or China, let's say, I could have gone to jail for the rest of my life. Yeah. Or been killed. We were getting eight dollars an hour. Yeah. It's mind blowing to me. When you're young, you're not that smart, right? You know. yeah, but you're, you have the, I think that's where ambition comes in, right? Like at some point in time when you're young, you're like, you know what? This knucklehead, I'm better than that guy. I can crush this guy. Watch this, you know? And I got to think that there is some sort of more than adrenaline, but, but, ego involved in it too. Like I can beat this guy or I can beat this woman. At least that's how I think. I don't know what that says about me, but I'm like, yeah, I can outsmart this guy. Was there any of that going on in your mind? Absolutely. And I'm a competitive guy. So there was like, you know what, I'm going to get this information. And my buddy who got the job in the book, his name is Pax. you know, Pax had gotten the job like two months ahead of me. And so we were very competitive with each other. And, you know, I would develop what we would call a ruse or a ploy, which is just how are we going to get this information? And I would develop one and we he would hear me on the phone let's say doing this ploy to get this information and then he would copy it and then I would hear him doing something and I would steal his thing and you know and so we were constantly like trying to one up each other to see who could get the most information And in the beginning, you know, we were getting a lot of kind of basic information that today theoretically is on LinkedIn, right? We would learn the company's organizational chart, right? And who ran teams and what they did. And, you know, back in the day before LinkedIn, you know, LinkedIn really didn't explode until after the financial crash in two thousand and eight. So LinkedIn really didn't start to take off until really about two thousand ten. So, you know, fourteen years ago. Right. But before that, there was no way for companies to know who was at a firm, what they did, what they got paid. You know, were they were they a rock star? You know, which LinkedIn still can't tell you. Right. You know, I mean. When people would go for an interview, let's say you were a salesperson and you'd go for an interview. You know, what are you going to tell the person you're interviewing with? Are you going to say you're a bad salesperson? No, you're going to say you're the best salesperson. You're one of the top salespeople at this firm. And what we learned is we could get the production numbers of sales teams at any company in the world. So we could tell you who's number one, who's number two, who's number three with the actual numbers. Statistics with their revenue, with their sales numbers. Well, think about how valuable that is to a rival corporation. If you can poach, if you can steal the top salesperson from your rival or the number two salesperson from your rival, you know, and then we would combine that. revenue information with how much these people were getting paid. We would get their salaries. And so you'd see, oh, salesperson number one, boy, they make good money. Salesperson two, oh, they make good money. Salesperson number three, oh, wait a second. They're a young up and coming future star. They're not getting, they're underpaid. We're going to steal that person. We're going to give them a big bump in their salary. They're going to leave this company. And now we just stole a rock star from our big rival. And at the end of the day, companies are about people. They're about the talent that you have. I always go back to football. I'm a big football fan. And remember when the New England Patriots lost Tom Brady and he went to the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, what happened? The Tampa Bay Buccaneers won a Super Bowl, right? Because they stole Tom Brady. I mean, he's a free agent, so it's a little different. But that's the same thing in corporate America. And that was one of the things in the early days pre-linked in, that was kind of a lot of the information we were getting was who are the top people? So our, our, our, our clients could steal them, man. It blows my mind. I, what does that say in your opinion about corporations in the American dream? I know it's kind of a big question, but like, are we, am I, am I romanticizing the idea that like your grandfather sold these horse and carriages, they moved up to this next level. And like, Am I just romanticizing the history of thinking that maybe we used to be a place that cared about our people and we were working together, even though competing, to try to become the best as shared goals and shared sacrifice, where now it just seems so cutthroat. Am I just romanticizing a past that was never there? Yes. I knew it. I mean, you know. we know how cutthroat sports are right you know you see coaches you know getting fired in mid-season and their record maybe isn't even that bad and we see things like that all the time corporate america is that on steroids right and sometimes people don't think that and corporations try to sell us on this idea that they have a a culture of this and the ethics of that and the morality of that And it's hilarious when I see CEOs or major executives on CNBC talking about company culture and company morals that I presented my stolen data directly to them. That is hilarious. Yeah. You know, I'm curious, like I. I want to kind of shift gears a little bit and kind of talk about the psychology of deception. In your memoir, you describe becoming one of the world's greatest corporate spies. At what point do you think deception became a survival mechanism, or did it become a survival mechanism for you? Look, I think when you're poor – and I started out as a poor guy. I paid for college myself. I lived on Kraft macaroni and cheese, three for ninety-nine cents. So when you're poor, you know, it's kind of like, you know, by any means necessary, you've got to survive, you know, and, you know, and so when I took the job, even though I knew it was, you know, morally dubious and actually at one point, my buddy Pax and I, we hired an attorney because, you know, we were young people. and we didn't want to go to jail. We asked the attorney, we said, look, you know, is this illegal? And the attorney said, he said, it's in the gray, the very dark gray. And so we, you know, we really tried to proceed with caution. Later, we got into some serious trouble and I don't want to spoil anything if your audience, you know, But, you know, we at one point we were being chased and hunted by, you know, a number of authorities with three initials in their names. Right. So, you know, but but I think as a young person, when you're poor, you kind of you're doing what you got to do to survive. And deception for me, you know, fortunately, unfortunately, was part of that. It's interesting that the word deception has a lot of negative connotations to it. But you could easily change out the word deception with persuasion or manipulation on some level. And I'm curious, like how – Let's talk about dual identities for a little bit. Like in the world of acting, which you've spent a lot of time doing, acting and meeting with people, you have to become the character. If you're Daniel Day-Lewis, you walk around in that character for like a month or something like that. The same must be true if you're going to ruse somebody at a company. I'm sure you got to do lots of research. You have to figure out the person you're talking to on some level. Okay, is this person, do they have a profile? Can you walk us through that? How do you prepare to be in that position? Do you do research? Do you check out the people? What's that look like? Yeah, I mean, you know, that's the thing that a lot of people, you know, they had this conception that, you know, we would, you know, because in the beginning we did go in person to do some of this rusing. We would go to a bar where we knew certain bankers hung out or we went to sports events, you know, and we would go to some of these things. But what we quickly found out was as actors that we could use the anonymity of the good old fashioned phone call to get people to tell us stuff that they would never tell us in person right um and of course we would impersonate um real people at companies and we would impersonate executives at companies right so I would see someone on cnbc and he'd go uh yeah this is bill jones and I'm the senior vice president of and I would hear that voice and I'd go well I could do that voice you know And then I would call someone up and go, hey, it's da-da-da-ba-ba. And then the person on the other end of the phone, and of course, a lot of times I would target the person on the other end of the phone so I knew that they would be levels below the person I was pretending to be, but that they would recognize the name, but they very unlikely ever had any direct contact with this person so that they would go, whoa, I've got this major executive on the phone wow, I want to get in good with the executives. So I'm going to be a team player because that's what we're taught in corporate America. And I'm going to help them out as much as possible. And so now I've got this person on the phone who believes I'm this executive. They want to curry favor. So they're going to help me and they're going to give me information. And even more, They're going to give me whatever I want to know. So obviously they have access to their internal directory. They have access to their internet. They can tell me anything I want to know. If it's corporate information for my clients or if I'm a hacker, they're going to tell me the architecture of their systems and how their systems are set up, which is going to make it easier for me or if I'm selling that information to a hacking organization. um it's going to make it easier for that firm to get penetrated now I never I never was getting information for hacking purposes right it's the same it's the same exact thing and and and we'll we'll segue a little bit into a very interesting topic which is ransomware attacks right which are proliferating and costing you know companies millions and millions and millions of dollars which they don't even publicize or announce because it's so embarrassing for their reputation right About a year ago, there was a major hack of MGM in Las Vegas. The elevators didn't work, right? People couldn't get into their hotel rooms because MGM had been told to pay a ransom. They said, no, we won't pay the ransom. And the hackers shut down a casino in Las Vegas. And that hack started with a social engineering or ruse phone call. Just like I described, you get someone on the phone, you pretend to be an executive and you get them to give you information, help you reset a password. And so most of the hacks, just like corporate spying, start with a social engineering phone call. It's amazing to me. Like on some level, we see these large corporations and they build themselves as these impenetrable forces. We've been around for two hundred years, but on some level, they're so vulnerable. You know, it kind of speaks to the human condition on some level. Yeah, I mean, I tell people all the time, forty five minutes. Give me forty five minutes. I can find out pretty much anything I want to know about your company. It's interesting that you bring up ransomware. It's so prolific. It happens all the time. And so many of these outages that you see, oh, we're just down for a little bit. You could probably bet there was a hack that happened right there. Absolutely. And it's scary, too. There was a hospital recently. A hospital was recently hacked. And the hospital was shut down. And the doctors and nurses are going back to writing things on paper. You know, so you think about how dangerous that is. And so that's one of the things that I try to speak to now when I'm on programs like yours and when firms call me for consulting is, you know, you need to train your people. You need to train your employees that there are people out there that are using the good old fashioned phone call. um to get the information that they then use to hack the system right and so if you're not training your employees if you're not preparing them for these kind of situations then it's not surprising then when companies get hacked and when companies get ransomware attacks and and when companies operations get shut down by hackers um and so I really now you know I kind of went from you know in the old days I was on the offense Now I'm on the defense, right? Now I'm trying to help firms, help corporations, especially to prevent that kind of activity. I'm glad you're doing that. It's, it's fascinating to think about the way, how big corporations are now too. It's almost like an unfair advantage for like a multinational corporation. That's so huge. Like they have no, the right hand has no idea what the left hand's even doing. Right. Yep. Yep. And we, and we utilize that to our advantage. So for example, I did the, I did the German accent earlier. Right. So I would be like, you know, y'all, this is Manfred into Frankfurt office. Right. And I'd be calling someone in Dublin, or I'd be calling someone in Tokyo, or I'd be calling someone in Chicago, right? And so they would look me up and they would go, oh yeah, Manfred runs legal for Germany, or he runs compliance for Europe. Oh boy, it's a little odd he's asking me for what he's asking me, but he's the head of compliance for Europe. There's gotta be a legitimate reason. And he's very funny. That accent is making me laugh. And he's on the same team. And so they tell you these things, even though there is a warning sign flashing somewhere in their head. Right. And that's what you talked about, about persuasion. Yes. And, you know, one of the things is when you're when you're a spy, when you're a hacker in these situations is you are always introducing the element of the ticking clock. the ticking clock, right? So I need this inflammation now. I have to have it now. We have an emergency. We're meeting with the regulators in Brussels. And boy, we're going to get in trouble. Boy, we didn't comply with this thing they asked us to comply with. Now they're asking us for all this extra stuff. Boy, I am overwhelmed. Don't worry, Manfred. I'll help you out. What do you need? And so all of a sudden, this person on the other end of the phone feels like they're really helping out a fellow executive that's in trouble that's under the gun right and so you're always introducing um I'm a high-level executive that's one thing and then you introduce the ticking clock right um uh that there's some sort of time emergency and so you're that those two things the power of being a high-level executive and the emergency you put them together and you can get somebody that is willing to do a lot of things for you. Yeah. And you, you had mentioned, um, the superior role in finding someone at a lower level. There's a great book by Dale Carnegie called Games People Play. I think it's by Dale Carnegie. And he talks about games people play. And if you think about it, we're all playing games. I'm the boss, you're the employee. I'm the doctor, you're the student. Or I'm the teacher, you're the student. And if a fun exercise that everybody can do within the sound of my voice is just change... When you find yourself in a conversation, you start asking the questions. You know what? I'll ask the questions here. And you can change who's responsible. You can change your tone. I'm curious, like, what are some other techniques? It seems like you've brushed on sense of humor. Sense of humor seems to be a great technique in order to change the pace of the conversation or gain trust on some level. At what point did you ever use sense of humor as a tool or a mechanism to extract information? And how do you go about doing that? Yeah, you know, I mean, there was always, you know, a joke. I mean, I think one of the first ones was, you know, you know, somebody would say to you, you know, how are you doing today? And I would always go pretty good if I didn't have to work for a living. Of course. Gain trust. Beautiful. Yes. And you said right away, you're starting out that, boy, we're at the same company. And boy, man, this job is hard. It's stressful. Boy, I wish I didn't have to work. The person on the other end of the phone is, of course, they wish they didn't have to work. Right. Right. And so right away, you're just cracking a joke. I would always know. I was calling cleveland I would know if the cleveland browns had won right the day before if there was some uh major accident on the fr you know whatever you know again that would be the research you would always do right that's why I said minutes um to find out whatever I wanted you know part of that minutes would be research right um where I would be figuring out who I wanted to call where I wanted to sit, who I wanted to say I was, where I was going to be located. And then once I figured out kind of those things, I would study the person I was calling, where they were located, what was going on in that area, what was going on with that company that day? Was their stock price up? Was their stock price down? Did the CEO just get arrested for drunk driving, you know, anything that I could use so that I would be so informed that the person on the other end of the phone would go. They're not even thinking that this person is rusing me or or possibly could be somebody they're not because they know too much information about the company. Yeah. But like you said, these companies are so huge. There's so much information even back in the day that was public. You know, you can read press releases right on their website. You can read their annual report right on their website. You can learn so much so that you really sound like you are you are an executive with the company. Yeah. And I'm curious to get your thoughts on it. It seems to me like I worked at a Fortune five hundred company and it seems to me the general consensus is there's an us versus them. And if you get someone on the phone or even someone that's an employee, maybe even lower middle management, they probably aren't talked to very nice by the C-suite executives. They're probably looked down upon as like these people are just numbers over here. Many really matter. We're making decisions up here. You get that person on the phone. That person is more than willing to share some information with you on that level. Is that you find that to be accurate? Absolutely. And that's what we would utilize is that exact thing. So, you know, I'm now senior vice president or executive vice president. I'm calling someone that doesn't have any title, you know, or is or is the manager. Right. There are levels below. And now they get this executive on the phone. And I would always say, you know, I would you know, I would be your best friend or your worst enemy. Right. So in the beginning, I'm cracking jokes. I'm your best friend. I'm a major executive, but I'm a really nice guy. Help me out. And then if somebody would start giving me a hard time and they'd start questioning me and maybe they were unsure and they got nervous, then I would start to try to put pressure on them, utilizing, again, the power of persuasion that, look, this is going to be good for you to help me because I'm a major executive and you're not, you know, and some some some people wouldn't crack. you know some people wouldn't and that was part of the part of the job you know and then we had this really fascinating thing where when somebody was not going to give us the information because this job was hard not everybody would give you the information um we would have this thing where we would this term we would use where we had to put that person to bed we had to put that person to sleep and what that meant was we've now got somebody that doesn't believe that we are who we say we are. And even more, oftentimes, those people were sort of up in arms, like, OK, you're pretending. I don't believe this. This is not true. And you could hear that they were about to sound the alarm bell. They were going to send out emails. They were going to go to corporate security. They were going to go to their boss. And they were going to spread the word that someone was calling for this specific piece of information. So my job now is to get them to not sound the alarm. How do you do that? So what I would do is they'd say, you know, I don't believe a word you're saying. I said, look, do you want me to send you an email? It says that spells out everything, everything I'm doing exactly. Yes. Yes. I want you to send me an email. OK, I will send you an email. I will have it to you within an hour. We'll have everything on it. It's going to come from a corporate email. Yes, it's going to come from my corporate email. Just just let me. I got one more fire I got to put out. I'll get you that email within an hour and it'll have everything in it. And you can calm down and know this is completely legitimate. And then the person would kind of go, oh, OK, well, yeah, I want that email. I want that, you know, and I'm sorry. I mean, I don't mean to be giving you such a hard time, but, you know, just send me email. Everything will be fine. Don't worry. I'll send you that email. Have it to you within an hour. Worst case, I'll have it to you by the end of the day. By the end of the day, worst case. Okay, well, look, thanks. Look, again, I'm sorry. I don't mean to give you such a hard time. No, no, it's fine. You're doing the right thing. You're doing the right thing. And by the way, I just saw something and I got another fire I got to put out. That email, if I don't get it to you by the end of the day, it'll be in your inbox first thing in the morning. First thing in the morning you'll have. Okay, no rush, but you know. Now, what have I done? I bought myself the entire rest of the day to get this information because obviously that email is never going to that person. They're never going to get an email, right? But what I've done is they're thinking, oh, he's going to send me an email. This is a legitimate request. He's a busy executive, but I'm going to get it and I'm going to know this was legit, right? And now I can move on to other people without this person telling anybody else in the corporation, right? And now I've got to get this information today. Does it become like addicting on some level? I heard a great quote once that said, what you do sometimes you do all the time. And if you get really good at extracting information from people, it seems like you would use all these techniques in like your personal life. Did you find that happening? Yeah. That's yeah. And I talk about that in the book too, because it is very addicting. Right. Um, and, and you realize that you could find out anything you want about your neighbors. You could find out anything you want about anyone. Right. Uh, And so I very early on recognized that that was problematic, right? That that was problematic. That if you're rusing your friends and if you're rusing your family and you're rusing your loved ones, that's not, that's not a road you want to go down. And so I really drew a line that the rusing was going to be for the job. And in my personal life, I had to, I had to really not utilize, you know that skill set because it's just too dangerous. Yeah. It's, it's interesting. And in some ways you realize what you're capable of and that can be scary. Yes. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. What, However, I think it would also be incredibly effective like in coaching actors or as much as you can help people with pen testing. I bet you could really help people understand relationships or conflict. I'm sure these are all byproducts of understanding the ruse is understanding human behavior. Right. Well, you know, you're reading people, right? You're reading people. And in the case of the ruse, the ruse phone call. I could hear in your voice when you answered the phone and you responded to me whether I was going to get information out of you or not. You could hear it. And a lot of times, if I heard in your voice that you were going to be tough, I wouldn't even give you my ruse because it would be wasted and then potentially you would sound the alarm. So I would I would very quickly get out of a call, you know, wrong number or, oh, I got another call. I got to call it. Let me call you back. And I would, you know, basically abort because I could hear I could read that person's vocal inflections that they were not going to be a good source. Right. And then other times I could hear right away, this person is going to tell me anything that I want to know. And I'm here to tell you for your audience, I'd say nine out of ten people, and that includes you, listener. You're not the one. Nine out of ten of you would give me anything that I want to know if I called you. It sounds to me to be a developed skill to be able to hear emotion in someone's voice. On some level, we can. We know when we pair someone's linguistic abilities with their face, with their eyes, with their gestures, like we can kind of tell what their emotions is. But it does seem like a pretty incredible skill to listen to what someone says and understand where they are emotionally at the point in time you're talking to them. Like that seems like a pretty valuable skill. You know, I think so. I mean, you know, we you know, we we've been blessed with with two ears and one mouth. Right. So I always think that, you know, because I am a talker, but I really focus and force myself to listen at least as much as I speak and ideally twice as much as I speak. Because you really want to make sure that in relationships and friendships and work relationships that you're listening more than you're talking. Because people, first of all, people like to talk. People like to be heard. So if you're somebody that can listen to someone right away, you're going to get a friend. You know, because now you're listening to someone, you know, and we all want to be heard. Right. And so in the situation of the ruse phone call, if I'm listening to you and we do a little tangent about the sports team that lost the other day and we bemoan that team and I listen to you vent. Well, after I've listened to you vent about the sports team that lost or listen to you vent about the difficulties in your job that day, which I would do all the time. Now you're my friend because I've listened to you and you feel heard. So now when I make a request to you, what are you going to do? You're going to help me. Right. Yeah, I think it speaks to the role of of empathy and persuasion. Like empathy is an incredible tool, which I wish more people had. But it is sort of this skeleton key which unlocks trust in a way. Yeah, and you made a good point earlier when you talked about beleaguered middle management, lower management people, right? That they're working really hard. They're often doing two or three jobs. They're not respected. They're talked down to. And so you get somebody that calls them that is, in my case, pretending to be an executive who is interested in them, who is... you know, being empathetic with them, they just love that. They just love that. And so then they are willing to tell you anything. And, and, you know, that was the thing that was, that was, um, surprising to me and also quite sad was, was how miserable most of these people are in their jobs, you know, um, and, and, and how lonely, you know, I had one woman say to me, um, I was calling her for information for many, many, many years. And we developed a sort of a friendship. And she's one of the main characters in the book. Her name is Zoe. And we developed this friendship. And at one point she said to me, she said, you know, she said, you're my favorite person at the firm. Now, we had never, ever met. We'd never, ever met. But She said I was her favorite person. Now, think about how sad that is, that her favorite person at the firm isn't really with the firm, right? Isn't really who she thinks it is. It's all a ruse. But yet she's so lonely. The corporation is obviously not a great place to work. People are not being nice to her, at least. And her favorite person is a telephone buddy that she's never met. Yeah. That's heartbreaking. She might as well have said, I hate everybody here and my job. Yeah. Yeah. And I think that's common. You know, I mean, your listeners will have to respond to you however they respond to you. And because I'd be interested to hear, you know, from people about, you know, on a scale of one to ten, you know, one being miserable, ten being happy. Where do you sit at your corporation, at your job? Like, you know, are you a one? Are you a ten? You know, I'd be very interested to hear where people are with that in America today. Yeah, that's a great question. Put it to the listeners and we'll definitely get some feedback maybe a little bit later. You know, there's an interesting book, another book called John Ronson wrote a book called The Psychopath Test. And in that book, he talks about the way in which leadership, especially at the high corporate level, self-select for psychopathy on some level. Like, do you have empathy? No. Perfect. We're going to elevate you here. Are you willing to get rid of all of these hundred and fifty people? Yeah, no problem. Like, have you in your personal opinion or I don't know what you get into with the book, but I think you deal with some high level executives. Is there any truth to that particular claim, in your opinion? Well, I mean, absolutely. I mean, the like I said, the fact that. That individuals that I presented, you know, stolen data to extract, I call it extracted data. The fact that I presented that to individuals that are then on CNBC talking about what a great corporate culture they have and you just realize the duplicity of these corporations, of these executives, and that they're willing to do anything and everything to promote the company stock price. Yep. so that they're getting a bigger bonus a higher salary you know or just not getting fired because you know these people have big jobs these people are making in many cases forget about millions of dollars a year tens of millions if not hundreds of millions of dollars a year that the c-level executives at publicly traded companies the amount of money they make with their salary their bonus and then the stocks is is incomprehensible We've touched on the, on the topic of identity a little bit, you know, and isn't it, isn't it interesting that people believe they are what they do? Like on some level, that seems like such a negative thing to me. And I guess it doesn't have to be, but if you believe that you are the thing that you do, and we get so wrapped up in titles, I am this, therefore everyone should see me as this. Maybe you could speak to the idea of, of identity and titles in the workplace. Well, look, the title, you know, you know, fortunately or unfortunately, is such a big deal at a company because, you know, the first thing people will say in the business world is, you know, I'm Bill Jones, vice president of tax, you know, or I'm Bill Jones, senior vice president of tax. Right. You know, people are introducing themselves, you know, when you're at an event or you're meeting people, you know. It's not just their name. It's not just I'm Bill or I'm Bill Jones. It's I'm Bill Jones and then their title and maybe even the company they work for. So you right away know, oh, he's important, you know, as opposed to I'm just Bill. And you see that a lot in corporate America is everybody is introducing themselves. And if somebody does introduce themselves and they don't say a title, then they're probably one of those beleaguered lower management, middle management folks that are doing two or three jobs and not getting the credit for it, not getting the title for it, not getting the compensation for it. and um so yeah you know it's it's kind of you know the title is a little bit like you know driving around in the um you know in the mercedes or the you know lamborghini it's it's the way to show off that you are you've made it you know you're above you know and that was one of the things you know you know We haven't really talked a lot about the morality of what I did. I was always I was always conflicted by it, you know, and I I I'm not justifying it. But the way I rationalized it, especially as a young guy, was, well, you know, I need a job. I'm poor. I need a job. That was one. And the other thing was, well, I'm just getting secrets. from one company and giving them to another company. And then that results in people getting better jobs because they get stolen away and all that stuff to rationalize it. But there was a third part of it, which was I had a little bit of a resentment of these major executives making so much money. Um, and so it was kind of, you know, in these corporations making so much money. And, um, so, you know, there was a little bit of that too, you know, cause I, I had, I paid my way through the university of Pennsylvania, which is a very expensive and elite school. And I was surrounded by people that, um, you know, went into the workplace and got huge jobs and made tons of money. And, and I was an actor not making tons of money. And, I was kind of like, God, you know, I mean, it seems like things are a little bit out of balance here. Like these guys are making, you know, one hundred fifty million dollars a year. I'm making, you know, you know, whatever. Fifty dollars, you know, whatever it was. Yeah. So that was another way I rationalized it was, you know, I deserve a little piece of the of the corporate America pie, so to speak. Yeah. I think that resentment, like I feel that resentment sometimes. I think most people do when you, you start thinking like, does that person really deserve that much money? But if you ask them, they'll be like, yeah, you know, I, I don't, I'm not a judge or a jury, but yeah, I think we all kind of feel that resentment. I think it's kind of warranted on some level. Is that too much? No, I say, you know, look, I mean, you know, look, we, we want people to be successful. We want people to be successful. We want to support, you know, but there's also, there's also the idea of giving back. um there's the idea of kind of sharing the wealth of of you know you know you you want you know if you're the ceo of a company you know you want your people to be well compensated you want your people to be well provided for because you're well compensated and you're well provided for it just it's just common sense you know but we see over and over you know part of the way corporate executives move up and get paid more money is to you know eliminate an entire division of a company and lay off eighteen hundred people you know what I mean um and things like that um you know that's where it starts to get it starts to get problematic you know um and obviously I come from a business family you know my right you know right um small business you know so I'm a big believer in small business but you know big business sometimes forgets um the importance of honoring your your your workforce Yeah, that brings up an interesting question. What I don't know if you have data for this, but was it was it more difficult, less difficult or the same amount of difficulty to get information from a private company versus a public company? That's a great question. That's a great question. So in over my years in rusing. We called all companies, small, medium and large, public, private, all over the world, Russia, Japan, China, South America, you know, you name it, we called it right. And some of the assignments we did, it was just incredible, you know, what I was being asked to to find out. And I would say private companies are a little bit harder, generally because they're smaller and they have fewer locations and the people know each other better. And so therefore it is harder. But look, when my clients would come to me with a list of firms they wanted me to penetrate and the information they wanted at those firms, know there would be public companies on there there would be private companies on there and my job was to get that information and I'm here to tell you that ninety nine point nine percent of the time I did we you you spoke a little bit about the morality of it and has has doing what you've done change your idea of the concept of trust I don't think so no I don't think so because you know you know what you know what trust is you know right and you know, I know what it is. And I knew when I was on the phone, rusing people that that was not, even though I was, I was building trust in a lot of ways, um, they weren't the right ways. Um, um, and we talked earlier about why I did what I did. Um, but, um, but yeah, I think, you know, we all know what, you know, we all know what, you know, at one point in the book, you know, my, my child at the time, um, uh maybe they were eight um and they heard me on the phone they heard me rusing and they said you know dad you know what you know are you a hacker or are you you know you know I said oh no no no you know I'm just getting information and you know and um giving it from one firm to another firm and it's helping people get better jobs you know I went through my whole song and you know and and my kid said but it's dishonest and I said you're right it is And that was kind of the moment when I said, I have to get out of this job. I have to stop doing this job. And that was kind of the beginning of extricating myself from this, from this from doing what I was doing. And I'll just tell you a funny story about when the book came out, one of the things that amazed me about the book, I mean, there were a lot of things that amazed me about Frank Abagnale giving me the most loving blurb, recommending me to his speaking agency, all of these, that was just shocking. But the thing I found the funniest was the book comes out I write an expose of the world of corporate spying and corporate espionage. And I cannot tell you how many companies reached out to me and said, Robert, we read your book or we listened to your book on Audible, whatever. We want to hire you to spy for us. You do know I've outed myself as a spy. I wouldn't be a very smart spy if I told everybody what I was doing and then went back and did it again. You know what I mean? It's like the bank robber that got away with the big heist but can't stop robbing banks. And then they get caught and they go to jail. I said, no, no, no, no, no, no, no. but that was and I think that just speaks to the corporations knew these people that reached out knew what I did knew that it was wrong knew that it was you know obviously morally and ethically uh dubious but also illegal you know and they didn't care they do not care these corporations do not care they want the information the c-level executives want to know anything and everything that they can about their rivals and they're willing to pay a lot of money for it Um, and they don't care about any of the legal issues. They protect themselves. Like I said, when they hire me to hire me through a consulting firm, um, through multiple layers, they pay me through multiple layers. Um, and, um, I shouldn't have been surprised by that, but I was. Yeah. Yeah. You know, I read, uh, I think on your book, there's a, there's a recommendation from John Perkins too, which wrote, uh, the economic hit man. And it's, it's fascinating to think about what goes on behind the scenes in the boardroom or, you know, you spoke a little bit about poaching particular salesmen, but I would imagine, did you ever have like a, the union or like the teams are trying to call you to get information on accidents and injuries, or were you extracting any kind of information like that? No, I never had that. And, you know, something I was surprised that I never was approached by any political organization. Yeah, because I really thought that the kind of rousing we did was ideal to find out stuff for political campaigns. Right. Right. And I don't think I would have done that because, you know, again, that's like a, you know, because now you're finding out who's cheating on their spouse or who's got a drug problem, right? Those things, which really, it starts to get, you know, even more sorted. So I didn't really want to do that, but I was surprised I never heard from anybody saying, hey, will you consider this? You know, because obviously that's out there, right? You know, I mean, political campaigns are really, You know, and I don't know who they're hiring for that. But those people are willing to get really down and dirty and find out the, you know, the most salacious information that they can about a political candidate. Yeah, it's interesting. You know, when I when you talk about. doing the ruse and then your, your kid hearing the, the image of a stone thrown into a quiet, calm pond comes to mind. Those ripples radiate outwards on some level. Was it difficult to sort of, you know, find your way back into like, okay, I'm done doing this stuff now, not, you know, to, to get the call back to a different kind of life. Like, how did you, how did you manage that? I didn't. I had a, I didn't, I had like a, I won't say I had an emotional breakdown, but I definitely had a period of depression where, not that I was depressed not to do this job anymore, but it was just like, okay, well, what am I doing now? And at one point I wrote a, one day I was sitting there and this voice kind of came to me and I wrote a suicide note. Now it wasn't me. Yeah, but it wasn't me writing the suicide note. It was this voice of this character that came through to me. And all of a sudden around this character, I wrote a book. I had been an English major in college before I became an actor. And I showed it to a couple of old acting friends and they said, wow, this is pretty good. You should write, you should write more. And that was the beginning of me starting to write. I started taking some writing classes. To my surprise, I started writing short stories. They were getting published in magazines. I started writing articles for newspapers and magazines. They were getting published. And I was kind of like, whoa, you know. And one day I was at a writer's conference and I wrote a little something about rusing, about this corporate spying thing. And people freaked out. And they said, oh, my God, like we didn't know corporate spies existed. We didn't know you did this. They said, you got to write a book about this, you know, and that was the impetus for writing the book. I had to wait until the statute of limitations expired for any crimes that I may or may not have committed. But once that statute, you know, passed, which was ten years, then, you know, I was able to publish the book and kind of, you know, tell the tales. Yeah. Have you received... did you ever get caught? Never ever catch you? Uh, you know, I'm, I don't want to spoil the book for the right. Yeah. Please don't. Or, or listeners. Um, but, um, um, but yeah, I mean, you know, there, there was, it was, it was, you know, it was Frank Abagnale ish. Let me just say that. Yeah. Yeah. There's a lot of, you know, a lot of hot water, a lot of, a lot of running and hiding. Yeah, it sounds like a total cat and mouse game where you're constantly trying to stay one step ahead and enthralling and exciting and the chase and acquiring information and, you know, being part of this thing that is this hot commodity that's sort of secretive. And, you know, on some level, it's secret agent-ish. Yeah, and, you know, you would get people, forget about angry, right? right you would have executives at companies furious especially the head of legal right uh general counsel uh that you know that you know someone they don't they're trying to find out who it is has penetrated their firm and has gotten xyz information and you know so that's where it gets into like the catch me if you can because now you've got the head of legal at a major firm with thirty attorneys on staff and corporate security people and a huge budget um and they're like we're gonna find this guy we're gonna find this guy we're gonna get this guy and and I'm not gonna say anything more about it right right right don't I like that that to me is so salacious and seductive in a way it's like you guys spend twenty million dollars on security and I just talked to your receptions and got everything what now yeah That's so awesome. I mean, in an executive type of awesome. I don't know. It's awesome to me to think that every individual is so powerful. And this idea of human connection, maybe longing in so many people, that if we just reach out and connect with people, we can really get the ideas out there and have a better life. And it also speaks to the sadness out there, man, of people living unfulfilled lives on some level. Man, what a roller coaster. Yeah, I mean, it was it was a roller coaster and I'm glad I'm kind of off of it. Yeah, of course. And but it's been fun reliving it, you know, you know, not only writing the book, but then, you know, you know, doing shows like this where people, you know, everybody finds a different part of the book interesting because, you know, the book's kind of like two books. It's a Hollywood tell all which we didn't really get into. Right. Because I was working with. Al Pacino and Paul Newman and George Clooney and OJ Simpson and all of these you know major you know major people you know there's kind of a forest quality I'm like with OJ you know right before the murders I'm getting hit on by Kevin Spacey you know like all of these crazy stories while I'm a corporate spy, you know, making all this money, being hunted, you know, you know, so, and then of course trying to have a personal life. So, yeah, so, you know, it's kind of two books, you know, and it kind of goes back and forth between Hollywood, Wall Street, Hollywood, Wall Street. So I think it's fun. I hope people like it. Yeah, I think people will definitely enjoy it. And I think if people want to hear about Kevin Spacey hitting on you or running with OJ, they should be definitely checking out this book. I don't want to dive too deep into some of the incredible stuff on there. Did you find there was a lot of crossover between some of the executive attitudes and the actors in Hollywood? Not the actors in Hollywood, but the producers and executive producers, studio people, very similar, very similar attitudes. You know, you know, yeah. I mean, you know that that. you know, there's this thing where, you know, they're not really gonna be nice to you. They're not going to be kind to you unless they think you have something to offer them. And I would like to live in a world where people are nice first without me having to prove that I'm worthy of your kindness, that we lead with kindness. You know, it's interesting to see the where you when you began using the ruse or you began using the telephone as a means of communication. There's a lot of I think it kind of echoes today. Now there's a lot of talk about people in a virtual world may not be communicating as well as in a room with somebody. But you've been you were using the phone to foster real deep connections with people. Do you have any thoughts on the way we're communicating today using the lessons that you learned in the past? Well, unfortunately, I think we're not communicating today, you know, and people are isolated. You know, the I think we're just learning now how look, this invention, the Internet, this call, you know, how we're seeing each other, different places, how other people all over the world are watching your show. incredible unbelievable mind-boggling right but there's also a downside to this technology and I think that it gets very easy um you know you see it when you're out in public you know you'll see a family sitting in a they're out to dinner for people and they're sitting there and everybody's on their phone right rather than interacting with each other right And the I think the phone, this technology is is unbelievably addictive. I think people are just now really starting to address that. And you're finally seeing schools recognize how addictive these phones are and how detrimental it is to young people and their development and their education. And the many schools now are saying, you know, phones aren't allowed, which I think is fantastic. You know, I know my kid is on the phone twenty four seven. I know, you know, you know, my nephews are playing video games all night long until three in the morning and then they're going to school and they're not doing as well in school because they've been up to three, you know. And for parents, it's an incredibly hard thing to do because, you know, in one sense, you want your kid to have a phone so you can reach out to them and you can contact them in an emergency. But, you know, so it's a real, you know, it's sort of a mess. And I think it has inhibited especially the younger generation in their ability to connect with people. Yeah, it's really easy to send an email and not have to face the consequences of the felt presence of the other. So I do hope that we can move forward in relationships. But I think that we have a real opportunity to create better relationships. And I think a lot of the work that you did sheds light on the psychology of relationships, the psychology of empathy. And I think you've really... done a lot of interesting things to help people understand relationships and stuff like that. But Robert, as we're coming up on this hour right here, what, what do you got coming up, man? What are you excited about? Where can people find you? What's going on? Oh, well, I mean, look, people can find me on my website. Uh, it's just my name, robertkerbeck.com. Um, and, um, I joke, but it's also true. I said, look, if anybody out there wants to pivot to a career in corporate spying, they're welcome to reach out. I'll give them some tips. There's a ton of work for spies out there. I'm out of the game. But the thing I'm most excited about is that I got a couple of new books I'm working on, and Ruse is in development for a TV series, which is pretty far along. very exciting um that you know the the book you know may may you know you know come to you know become a limited series which is something that I never ever would have thought like in a million years I mean even when I was writing the book I never thought like oh somebody's going to make this into a tv show like but the fact that that is in process is is like I said I I just can't believe it and I'm really excited and you know fingers crossed knock on wood I think I read somewhere that you're spotlighting some local authors in your area, too, hoping to shine some light onto their books. Oh, yeah. So I run a literary salon at Soho House Malibu. Again, if any of your listeners are in the L.A. area, they're more than welcome to reach out. I'll have them come as my guests. And the authors that I've had come, I had John Densmore, the drummer for The Doors. I had Dennis Lehane, who wrote Mystic River and Shutter Island and Gone Baby Gone. I had Serge Tonkin, the lead singer for System of a Down. I mean, as a matter of fact, tonight I have Laura Dave, who wrote The Last Thing He Told Me, which is an Apple series with Jennifer Garner. So, you know, I've just had these amazing authors and it's a real labor of love. I get to interview them and talk about their books, just like you're doing with me now. I do that in person with the ocean right next to me. It's so beautiful. John Densmore from the doors. That sounds like an amazing conversation. Did you guys, what'd you guys talk about? You know, he wrote a, he wrote a memoir and his memoir was about the friction between You know, obviously, Jim Morrison died from alcoholism very young. And the other two members of the band, they wanted to sell the music for commercials. And John felt like that was commercializing the Doors history and the Doors. You know, he didn't want a Doors song for a car commercial. He had no problem with them. Right. Yeah. He had no problem with them using the music in movies, you know, because the doors were in apocalypse now their music, um, or on TV shows like in artistic venues, but he just didn't want, you know, and, and he, and, you know, he felt like they were, they were, were making so much money from the Doors catalog. None of them really needed any money. They were all rich. But the other two members wanted to do that. And they sued John Densmore. And they went to court. And they had this huge, amazing trial, which John documents in the book. And eventually, John won the trial. Um, and prove that the, the doors original agreement, uh, was that the music would not be used in commercials. Um, and it's just a fascinating book and he's a fascinating guy. Um, and so again, that that's the kind of conversation that I'm having with these salons. It sounds amazing. How are you? Are you okay on time? I had a couple more questions, but you've already been really generous with your time. If your audience isn't bored of me. Yeah, no, not at all. Okay. I just wanted to make sure. Cause sometimes I just, it's, I always want to be thankful for the people. I think we're beginning to touch upon this idea of storytelling on some level. You as a storyteller, you've lived a story, you wrote a book about a story and now you have this other dimension where you're interviewing other storytellers. Can you talk about the power of storytelling? Like why it's so sort of contagious and why it's so captivating and why you find yourself in the midst of it right now? Well, first of all, the thing about a story is it's usually a tale of of someone else. Right. Yes. You know, it's it's it's something you haven't ever experienced. It's something you don't know about. You know, one of my authors recently was a young woman named Sophia Sinclair. She's from Jamaica. And she wrote this story about growing up as a child with a father who was a Rastafarian. now I did not know anything I mean you know the only thing that most of us know about rastafarian is bob marley right and um you know that's all we really know right and I didn't understand was it a religion was it a movement was it you know like you know what what is being a rastafarian and how you know and so that book was fascinating to read her book it's how to say babylon uh by um sophia sinclair and um you know, just the opportunity to learn like, you know, so much about that. And the same thing with John Densmore to learn so much about this interplay between the band members for all of these years, um, you know, and the, and the struggles and the issue of, you know, uh, artistic integrity and compromise and commercialism. And, you know, so, you know, you, you get these fascinating, um, uh, authors telling these fascinating stories because they're, and even if it's the, you know, those were obviously nonfiction, but even if it's a fiction book, you know, cause tonight I have Laura Dave who wrote the last thing he told me, and this is fiction and it's a thriller and suspense and twists and turns. But, you know, there's still things in there that you're you want to know, like, how did you come up with that? You know, like, how did you how did you figure that out? And how did you decide to tell the story that way? And how did you pull it off? You know, so it really is is enjoyable for me to get to interview these people and ask those questions. It's almost like a different dimension. It seems like when you get to be part of a story, you know what it is. It almost it almost seems like a. like a rite of passage on some level. You know what I mean by that? When you look back into like a ceremony, a rite of passage, like a young man gets to watch his older brother go through a ceremony to become a man. The older brother gets to go through the ceremony. The father gets to see his son go through it. The grandfather gets to see many generations happening to it. And on some level, it sounds to me like that's the phase of we're in. Like you've already told your story about how you – You had this incredible story that happened, and now you're making this transition into being the person that facilitates the story. Do you think that in the Western world, we sort of have gotten away from this rite of passage in its own story? I know that's kind of a, I didn't really phrase that question the right way, but in the Western world, it seems like we suffer from an absence of rites of passage. And all these stories you're telling seem to me to be rites of passage in some way. What do you think about that? Well, I love that idea. There's like you're sort of touching on mentoring there. And yes, yes. So, you know, when I was a young actor and this is a chapter in the book I was working with, I was being directed in a play at the Actor's Studio in New York by this guy named Jim Lipton, James Lipton. And as you may recall, James Lipton created this TV series, Inside the Actor's Studio, which ran on Bravo, was a huge hit, twenty years, won Emmy Awards, and he interviewed everyone, you know, Al Pacino, Paul Newman, Julia Roberts, Bradley Cooper, you know, on and on and on, right? I was with James when he first came up with that idea. And I was the lead in the play he was directing. So we spent a lot of time together. And one day we were sitting backstage and he said, you know, Robert, I have this idea for a show. You know, let me tell it to you. Do you think this would be an interesting show? And he said, you know, my idea is I interview actors about pivotal moments in American movie history. Do you think people would be interested in that? Yeah. I said, James, people would love that, right? People would love it. That's a great idea. You should do something with that. And at the time, he didn't really know anybody at the actor's studio. And I was a member of the actor's studio. And he said, can you introduce me to Paul Newman? Because if I could get Paul Newman to sign on and be my first guest, that would give me some credibility and blah, blah, blah. So long story short, and again, I don't want to spoil the book, that connection happened. Paul Newman was James' first guest, and that gave the show some wind because people wanted to hear Paul Newman talk about his movie roles and how he prepared and what he was thinking. And obviously the rest is history. So when I came up with this idea with the literary salon, it wasn't really me coming up with the idea. It was like, I'm just going to replicate what James Lipton taught me. And I'm going to do the same thing, but with authors, you know, at Soho House, Malibu, by the ocean. I'm going to do the same thing. I'm going to ask the same questions. Like, how did you come up with this idea for the book? Or what were you thinking, John Densmore, when your bandmates, when you got the packet, you know, the giant document from the lawyers that your bandmates were suing you? Like, what was your first thought in that moment, you know? um so those are the kind of things that you know people are like that's fascinating you know like you know the two of the members of the doors are suing the other member of the doors and they've sued him for like thirty million dollars that way you know like she was gonna go bankrupt if he lost that suit you know and he fought it all the way for years for years and he won um so it's you know to be able to have conversations like that it's just you know What's your, like, do you, it sounds to me there's like an Ariadne thread that runs through so many of the stories we're talking about. And it's this one of relationships. It's this one of overcoming adversity. Like, what are some of the stories that really call to you? Is it the hero's journey or is it this, you know, call to beat corruption? Or what about you personally? What are the stories that call to you? You know, again, I think what I love to read and watch are books and programs that are showing me something that I haven't seen before, you know, whether it's, you know, like I said, you know, with Sophia Sinclair, it was Jamaica and this Rastafarian culture, which, you know, was fascinating. And then, of course, like with John Densmore, you know, going inside this lawsuit about the band and then it went all the way back to the beginning in the history you know things like that you're just like this is just incredible you know to to read this you know and the same thing with television and films you know I want to see a world you know that I haven't seen before or individuals that I haven't seen before or you know um so you know that that's what I look for is something that is is fresh um because that's always exciting when you when you know So, you know, I mean, that's nothing against, you know, your good old, you know, I don't know, conventional rom-com or, you know, I'm not putting those other things down. It's just in general, those things don't appeal to me. Do you find that getting to read other people's stories, like you read their book, that the world you make up in your own mind usually exceeds the world that you see in the media? You know what I mean? Like sometimes they'll make a movie based on a book and you watch the movie. Like that's a good movie, but I sort of like the vision I had in my head more. Yeah, well, look, you know, almost anything that you see on television has a sort of hyper realism. So it's not realistic. There's like a like an extra ten percent added or twenty percent added because, you know, the powers that be don't think you're going to sit through if it's just kind of realistic. um you know so the idea of like a realistic tv show or a realistic movie it it doesn't really exist that much anymore everything it's like you know remember the movie spinal tap uh my amp goes to eleven you know so all the tv shows and the movies are turned up to eleven right Yeah. It's interesting to think about the mental picture that we paint for ourselves when we read the work of someone else. And if perhaps that skill is atrophied because of so much, so much that has gone out there, what do you think it is atrophied in some level? Cause maybe there's less people reading. You know, I do think that, I mean, you know, one of the things that's happened with this boom in high quality television, which I enjoy, I enjoy as much as anybody else. Well, I think one of the things is, is a lot of writers have gone into writing for TV and in the past they would have been writing books and they're not writing books now. So, so, you know, that is a little bit of a shame because I don't know, you know, I mean, you know, at the end of the day, you know, TV shows kind of come and go and there are some TV shows we remember for fifty years, but they're very few. But, you know, but books kind of stick around, you know, because, you know, when you buy a book, you know, you buy a book and you keep it and you put it on your mantle or you put it in your bookshelf. And, you know, so it seems to me the books have a little bit of a longer life than kind of a movie or a TV show, you know, but that might just be me. Yeah, no, it makes sense. What are, do you have any books that like you keep on your bookshelf that you sort of return to from time to time? Like sometimes I, I have, um, over there, if I'm looking at mine, I have like a couple, I got the Carl Young book and a couple of books that people had sent me, but I find myself always going back to some Terrence McKenna books or just some obscure authors. Sometimes it really inspired me. Who are some books or some authors that you returned to, to be inspired? Well, you know, I mean, I go back to like, you know, Cormac McCarthy, you know, No Country for Old Men, The Road. I mean, you know, those are books you can go back to and and, you know, be freaked out by them over and over. They're just they're so good. They're so intense. So, you know, that's one that I really like. But in general, because I have this literary salon and I'm getting sent books all the time, I'm constantly reading new books. So unfortunately, I don't have as much time to go back and read old books because I've got a giant stack of new books, which I love reading. Do you see, because people are sending you new books and you're talking to all these fascinating, cool people, do you see any trends or things that you see possibly as trends as our culture moving forward? Well, there are a lot of memoirs. There are a lot of people writing memoirs. And there are a lot of memoirs written by pretty darn famous people that nobody reads. And I'm going to have to wrap it up soon because I think my wife's got some construction people coming to the house, which I didn't know about. Got it. But I'll tell you a funny story. So I'm at Soho House Malibu. You know, Soho House Malibu, there's celebrities running around and I'm about to do my salon upstairs. And so people are coming up to me and they're saying hi. And this guy sees me and he sees I'm kind of the center of attention because I'm hosting the salon. And he comes over and he's like, who are you? Who the hell are you? Because I'm really nobody. But he looks very familiar. And he's like, who are you? Like, you know, like, I don't know you, but you should know me. And I'm looking at him and he looks so familiar and his voice is so familiar. And all of a sudden I realized it's Steve Guttenberg. You remember Steve Guttenberg? Like he was an actor, three men and a baby. And he was kind of like a big, you know, police academy. I think, right. He was kind of a big star at one point. And he introduces himself and I introduced myself. And then he goes, I've got a memoir. So Steve Guttenberg's written a memoir. Now he wanted me to have a salon for him. And so that's my point is that there are a lot of people now writing memoirs. So that's kind of one of the big trends is that everyone is writing a memoir. Most of them don't get read even by people like Steve Guttenberg. I mean, I don't think he sold very many copies of his book, but everybody's writing memoirs, so. Yeah, it's interesting. I wonder if he's related to the printing press, the Gutenberg press. Anyways, my mind will just keep racing. You know, Robert, fascinating conversation. I think every book within the sound of my voice, go down, check out the book, Ruse. It's all about being a corporate spy. Robert said, reach out to him if you want to learn more about what it takes to be a corporate spy. I think it's fascinating information. And I think that the story people will be blown away by. We only covered a little bit of it. It's out now. You can buy it on Amazon. It's on Audible. The book is called Ruse. Go down, check it out. That's it, ladies and gentlemen. Have a beautiful day. Yep, that's it. Thank you so much, Robert, for everything. Have a wonderful day. Thank you. Okay. Bye-bye.

Creators and Guests