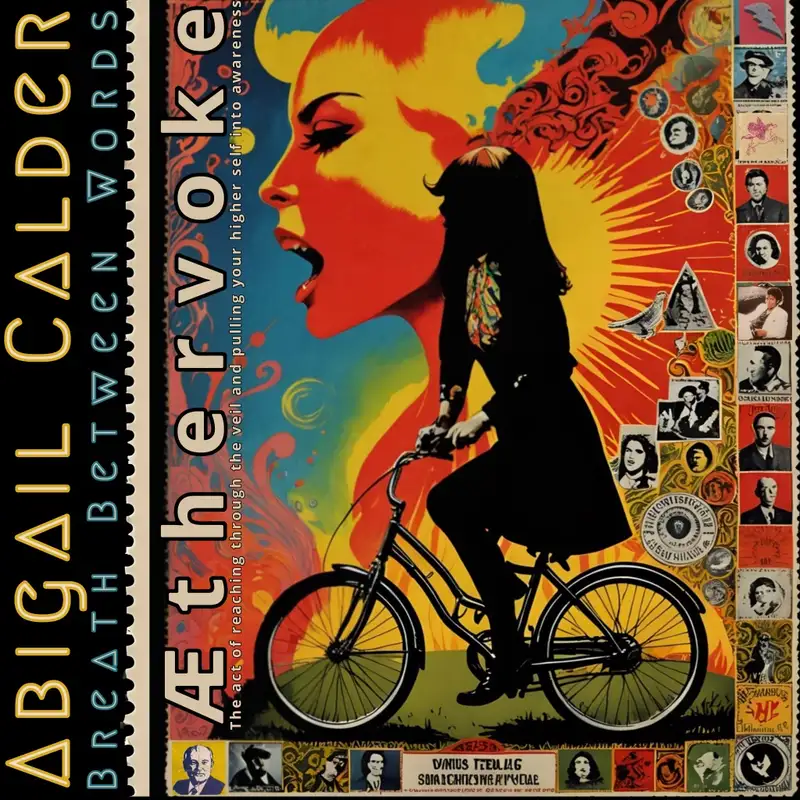

Æthervoke: Abigail Calder on LSD, Consciousness, & Unlocking the Higher Self

ladies and gentlemen welcome back to the true life podcast I hope everybody is having a beautiful day over here in the states it's mlk day so we're celebrating dreams and going to the mountaintops and I just want to take a moment to introduce someone who has looks like they're living their dreams so welcome everyone to another insightful episode of this true life podcast today we have the honor of hosting Abigail called her a brilliant young mind at the forefront of psychedelic research. Abigail is not just a PhD candidate at the University of Freiburg, but a beacon of light in understanding the intricate dance between psychedelics and the human brain. With her work on neuroplasticity, particularly how LSD can reshape our neural pathways, Abigail is pioneering a new wave of science that connects the dots between consciousness, well-being, and the mystical experiences psychedelics can offer. But beyond her academic accolades, what truly sets Abigail apart is her passion for demystifying these complex subjects for everyone. Through her roles with the Alps and Mind Foundations, she's been a bridge between the science lab and our living rooms, making psychedelic science accessible, understandable, and deeply human. Her dedication to exploring not just the highs, but also the potential pitfalls of these substances shows a commitment to integrity and safety in science. So without further ado, let's dive into this conversation. Abigail, thank you so much for being here today. How are you? Wow, thank you, George. That was something. That was the nicest thing anyone said about me in like a year. It's so good to be back. I think I was here, what, over two years ago, two and a half years ago. It's good to see you. Yeah, the pleasure is all mine. It's good to see you too. And you've been busy. You've been publishing papers with some heavyweights in the psychedelic field. You've been touring. You are... working at the alps foundation the mind foundation like where should we start at abigail um well I thought we would start where we left off last time okay um when you made a connection between me and one of your other guests and that led to something pretty cool It did. Isn't it interesting how it seems to me that so much of which we are interested in, and perhaps we share an abundance of interest in, is this connections, whether it's neural networks, the way mycelium grows. But it's interesting how you can make those connections, and they're so powerful, right? Just introducing you to Dr. Rick Strassman, you guys go off on your own journey, and you create this new thing, and you bring back this water for the community on some level. Let's talk about what you guys created over there. Yeah, I mean, for me, it's about connection, but also just adventure, man. Like I sit down for a podcast with you. I have no idea what's going to happen. And a couple of months later, I get to work with Rick Strassman. That's a freaking adventure. But yeah, so last time I was here, you just had Rick Strassman on and he was looking for someone to update his hallucinogen rating scale. which I had barely heard of at the time, but it was a questionnaire for measuring psychedelic effects, right? And there's a few questionnaires like that, but the hallucinogen rating scale is a bit different from some of the others because it's broader and it has simpler items. I think it's easier for people to fill out after a trip as well. And after getting to know it, I decided I actually like it better than the skills I've been using, so I've now switched. And he was looking for a doctoral student who had some time, which I didn't, but that didn't stop me, who had some time to update it because it was kind of old and it needed an update. And then so we sat down and talked, and I think we got on immediately. He's very down-to-earth. I love how humble he is, especially for how famous he is. That's a really great quality. And I think he's really easy to talk to. And yeah, then we collected a lot of data from, I think in the end we had eighteen different studies that had used the hallucinogen rating scale. And we collected data that Rick had from his DMT studies, but we also had data on psilocybin, ketamine, salvia. MDMA and some similar substances, THC, some stimulants. One person in Germany gave people meth and then gave them the hallucinogen rating scale. And yeah, and ayahuasca, of course. It's sad for no LSD, but we're now collecting the LSD data. And basically what we wanted to do was we collected all of this data. We had like a thousand data sets in the end. Also some placebos where people got nothing. And we wanted to see how this hallucinogen rating scale would behave with different drugs. And then we published this paper analyzing all of that. And for me, this was really spectacular. And I kind of couldn't believe it was happening because I came across Rick's research when I was in high school. And now I'm publishing a paper with him. So thank you for that, George. Yeah. It's so wonderful to think about the idea that relationships are the real currency. You know what I mean by that? Getting to know someone, even on a superficial level, or getting to know someone and then being able to do something for them, I think is one of the greatest things we can do as friends, as family, as people. And I think the more people that do that, the better the world's going to be and stuff. And in some ways, I think that the HRS and some of your work speak to that. Maybe you could talk a little bit more about the HRS. You introduced a whole category of meaning in there, which I thought was tremendous. And I know it's kind of a broad subject, so would you be so kind as to maybe paint a picture for everybody? What does that mean to add meaning to the HRS? What is that? Stop me if I talk too much statistics. Not at all. So basically, the HRS has a hundred questions on it. It's kind of long. And the questions will be things like, While you were tripping, did you feel anxious? Did you have childhood memories? Did you feel loving is one of the questions. There's a hundred questions. And we wanted to do a statistical procedure called factor analysis, which is pretty standard when it comes to analyzing questionnaires, just to see which of these items group together. So which of them tend to go together? And we found sort of eight groups of items that go together or eight factors. And one of these was a group of items that we decided to call meaningfulness. And it was a bit, it was kind of a special group because it was the one factor that was specific for psychedelics. So you remember we had all these different drugs. We had THC, we had stimulants, we had ketamine and salvia, and we had MDMA. And psychedelics scored higher, so people had more meaningfulness in their psychedelic trips than in all these other types of drug experiences. So this factor is kind of what makes psychedelics unique. And if you look at the questions that are in this meaningfulness group of questions, it's things like having paradoxical feelings is one of the items, or having insights into something, or I think childhood memories is in there, thoughts of the present or recent past, a lot to do with this altered perspectives on things, often altered perspectives in some kind of emotional way. And that was all loading together on this meaningfulness factor. And that seems to kind of describe what psychedelics do that's unique that other drugs maybe do less of. So I, I'm reminded of Francis Crick in a way, like how he came up with the idea for – I think it was him who came up with the idea of the double helix while he was on a trip. Did you come up with some of these questions while you were working with these different substances? I don't know if you can even talk about that, but it just seems – how did you come up with this idea for Meaningful? Because I think it's an interesting category. Yeah, no, so Rick came up with these, and maybe this is actually important to mention, like these questions were all thirty years old. So the questionnaire's been around for thirty years. Rick came up with these, I don't know what state he was in when he came up with these, I was not born, and he didn't tell me. But I think he was probably sober because he did it in kind of a statistically rigorous way. Try doing that on LSD, I don't know. So what he did was he interviewed people who were very experienced with psychedelics, I think particularly DMT, but psychonauts. And he had them describe their experiences. And he made a big list of potential questions through this procedure called psychometric interviewing. And it was more than a hundred questions, I think. And he used that list to make the questionnaire while he was running his experiments with DMT, these famous experiments from the nineties. And so based on which of the questions scored higher after DMT, he picked the ones that were the most appropriate for the questionnaire. And then he got his questionnaire. And that's actually something that I really like about the hallucinogen rating scale that some of the other psychedelic rating scales don't have. Some of the others, like for example, the five DASC, five dimensions of altered states of consciousness, or actually the current version is the Eleven Dimensions of Altered States of Consciousness. It has a bit of a different history and there have been some good psychometric studies done on it, but originally where these items came from was this guy who just thought of them. And they weren't specific to psychedelics. The guy, his name was Dietrich, it was back in I think the seventies or eighties. And he was trying to discover items that would describe any altered state of consciousness, including things like dreams and out-of-body experiences, trance-like states, stuff like that. And it wasn't specific to psychedelics. And so that questionnaire, because it wasn't developed with psychedelics, is kind of missing a few things that the hallucinogen rating scale has because it was developed using psychedelics. So to answer your question, maybe Rick wasn't on DMT when he was doing the scale, but the study participants were. Totally. I'm going to throw out this phrase here, Abigail, and I'm curious to get your thoughts on it. Quantifying the ineffable. What do you think of when I say that? Yeah, I think there's always a tension here because it's an impossible problem. We are trying to do the impossible, but we're doing it in a way that's useful. Kind of how, like, you spend every day trying not to die, and you will, but every day you try not to in a way that's useful for you. We're never going to be able to fully quantify the ineffable. Ineffable. But in order to show effects in a scientific paper, we try to come up with something that's good enough, that captures enough of what we mean that we can show, for example, there's a difference between LSD and placebo on our questionnaire. And we can prove that to people who were not in the room when we gave people LSD, people far away. It's all about statistics, man. It is. It is. But sometimes there's – it's always those pesky variables that you can't control for. It seems like there will always be those there, but maybe that's the magic. Maybe that's where some of the magic is done. But I do think that the HRS that you guys are working on goes a long way in helping people maybe better understand things on some level because there are these areas where you can't – there's no words for them. But the questionnaire goes a long way in understanding meaning. You've got some really cool graphs in there. So maybe you could talk about those for a little bit, like some of the charts and graphs you got in there. Yeah. Rick loves to say that he doesn't like the word ineffable because even though it's supposedly ineffable, people never shut up about it. There's a bit of truth in that. Yeah. So I think as scientists, we just have to be aware of our limitations. Um, The HRS is a way that we can extract some pretty interesting information from somebody's psychedelic experience, but that's not to say that it can assess every bit of the psychedelic experience. You can't read through these questions and see some scores and know what it's like to take LSD. but we can use it as a tool to extract some useful information. And so probably my favorite part of the paper was actually this meaningfulness factor that we, using the data that we collected and our statistics, we can figure out which types of drug effects go together and how that differs between drugs and what's maybe a bit unique to psychedelics and what's a bit more unique to MDMA, what's unique to THC, et cetera. Maybe you could dive a little deeper on that. What did you find out there and what are the differences? Maybe I talk about the other factors as well. So let's see if I can remember them and I have the paper pulled up in case I can. Yeah, absolutely. One of them was visual effects, which is probably pretty obvious. So all the questions on there were about hallucinations. Um, one of them was what we call dysphoria. So you might also call it the bad trip factor. So these are the questions that are things like anxiety or fear of dying or confusion, also some like unpleasant physical sensations, um, things that people that are unpleasant that people tend to feel when they're having like a bad trip. Um, there was also a factor that we call euphoria, which was kind of the positive affect factor. So people scoring high on that would put that they feel euphoric and that they let's see what else was on there. Some other positive emotions were on there. I forget exactly which ones were happiness. And then there was a kind of similar factor, which I thought was interesting because it was separate from euphoria and we called it liking. So basically how much people like the experience and want to repeat it. And you see how that could be a separate factor because you might have a fun experience that you don't necessarily want to repeat, maybe because you're tired and it was too much. You might also have a bad trip that you would repeat in a year. And so those kind of dissociate from each other. And then we also, we had a factor that we called auditory and minor senses. So this was basically mostly auditory effects, like changes in how you hear things, changes in sound, but also some changes in the other five senses that are not visuals. So basically all the five senses except for visuals were on there. And this is something that is in the HRS, but not necessarily in all the other psychedelic reading skills, because I think most of them assess vision and auditory stuff, but they don't assess taste, smell, or touch most of the time. And then we also had one that was called somesthesia. So basically embodied sensations, physical sensations. And this is also something that's really missing from a lot of other psychedelic rating scales, but it's really important for psychedelic experiences, right? I mean, there can be some very strong physical sensations. When we have people on LSD in the lab, for some of them, it's very, very bodily, very, very physical. And they're very much in touch with their body. And so I was really happy to see that. And then I think the last one we called volition. So basically how much control people have over the experience. We know control is a big issue in psychedelic experiences, right? Was that eight? I think that was eight. I think so. That was eight. Can you talk about the dose range? Were there different heights, different dose ranges? Were people feeling these different ones? Maybe you could talk about that a little bit. Yeah, so people had a range of doses like for DMT they had between I think, point zero five milligrams per kilogram and point four, which will probably not say much because it was IV. But point four is a lot. Zero five is barely any. Point four is a dose that was high enough that Rick concluded it was just kind of unnecessary. So that's the span. It was also funny to see on the graph on the factor liking, like how much people like the experience. As you go up with the DMT dose, liking goes up until you get to point four, then it goes back down. Yes, so people don't need that. For psilocybin, there was also a good range of doses. We had some of the data from one of the Johns Hopkins studies. And there, the highest dose was also quite high. And then the lowest dose was maybe not a microdose, but kind of a mini dose. And especially for those two, you can see a nice dose response curve on the graph. So you can see that for most of the factors, as you up the dose, the scores on the questionnaire go up to with a few funny exceptions. Did you do a deep, do you guys do like a debrief of people? Like, like was, are you at Liberty to talk about someone that took like a huge dose and then like what they saw and what they were thinking about or any, any sort of stories from there? Well, some of them are in Rick Strassman's book. Like this is old data that we had that we were analyzing. And then some of it's published places. And for our new studies, we do have sometimes trip reports. Yeah, that we either analyze or just have for our records that people give us. Yeah, I can't think of any crazy stories off the top of my head, because especially with this old data that I didn't collect myself, you know, I wasn't in the room with people. But yeah, I remember in Rick Strassman's book, there were some pretty crazy stories of like aliens and I don't know what else. They're doing some interesting studies over there. I think, I forgot where I was hearing it, but aren't they doing some like intravenous DMT studies? Are you aware of some of those? Yeah. Yeah, they're doing some in Switzerland. I think in Basel, although I wouldn't swear to it. Yeah, no, they definitely did it in Basel. At Matthias Lichty's lab in Basel. They did more than one intravenous DMT study. And they did one actually where the participants could decide when to stop the infusion or whether they wanted to go up or down with the dose or something like that. So they gave the participants control over the DMT. And when you have intravenous DMT, because it's so short acting, if you change the dose or stop the infusion, then it stops pretty fast. So it's kind of nice to have this control over the experience. I think they just published that one actually. I got to get on it. I got to read it. It sounds fascinating. What does this all mean for neuroplasticity, Abigail? I know that you eat and breathe this stuff. So what are you most fascinated by? Is the HRS connected to neuroplasticity or some of these experiments? I know you've got other papers out there, but what does this mean for neuroplasticity? That's a really good question. So I think I would rephrase the question slightly. Is the subjective psychedelic experience related to any changes in neuroplasticity? that you have after and so I came on here to talk to you because I'm at the end of a project and we're just publishing it and I love being at the end of the project because then you can look back on the whole thing and go back and thank people and just just have a lot of gratitude um I have to admit I can't fully answer your question but I was in this mindset again today because of a neuroplasticity project My main PhD thesis is about LSD and neuroplasticity. And I can't say anything at all because it's all preliminary. But today I was really analyzing some of the data for the first time. And also just looking back on the whole thing and feeling gratitude for my data and I better shut up before I say anything else but like one of the things we're going to look at is okay let's say we find a change in neuroplasticity is that it all correlated to how strong the subjective effects were And, you know, for us, people had the same dose. They had a hundred micrograms of LSD base. So quite strong, good Swiss quality LSD. And the dose is always the same, but the subjective effects can be quite different. You know, that's a dose that for some people is even a bit underwhelming and they think it could be more effective. And then for some people, it completely knocks them out of the universe. And they're like, okay, I could have done with less. And then for some people, it's perfect. And so it will be interesting to see if changes in neuroplasticity are at all related to the intensity of the experience, which might be, I mean, part of that is going to be biological. Like how good is your body at breaking down LSD? Some people at the same dose of LSD will get a larger hit to the brain than others just because of how their body breaks down LSD. but also there can be differences in the receptors in the brain that react to LSD. Some people might have a higher concentration than others. And so it'll be really interesting to see if that's at all related. I have no idea what we're going to find, but I'm really excited. Nice. Audrey says, Abigail, I cannot wait to discover your neuroplasticity study. You've got a lot of fans out there. I have one fan, George. One. No, you don't. You got tons of them. You got tons of them. Like I always see all your posts. You get like all these people commenting on there. I saw you with Jules a while back talking about some of the negative consequences. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. That's another big research area for us. Yeah. The dark side. It is. It doesn't really get that much. People don't like to talk about that too much because it kind of shines or puts a shadow sort of on the whole. the whole idea of it, but there's some real consequences sometimes, isn't there? Yeah. And, you know, I think there is a lot more research on that lately. Just over Christmas, I think I was looking at new publications on my Christmas vacation, which is bad and I shouldn't do it, but I do it anyway. And there were like four or five new publications just over those couple weeks of holiday break that had to do with adverse effects. So we're seeing a lot more research into that. um, as long as it's all fair and scientific, I'm all for that. Um, but yeah, so another thing we did with this year was, um, mainly out of self-interest, we were doing this LSD study and we wanted to assess adverse effects. And so we looked at rating scales for adverse effects and the ones that we found were kind of just not suitable. They would have things on there that had nothing to do with psychedelics at all. Like, um, did you experience urinary incontinence after LSD? Or just some other crazy thing that you never heard of anybody experiencing after psychedelics. And they were long. They would have like, seventy items, a hundred items. And they're just kind of made for general side effects of any drug ever. And we thought we want to make a scale that's specific to psychedelics that really only assesses the side effects that are the most common or the most troublesome for psychedelics. And so we made that scale and published it this year. It's called the Swiss Psychedelic Side Effects Inventory. And now we get to use that in our studies too. So that was a pretty rewarding project to work on as well. And now that skill is out there for people to use. I'm stoked that you guys have created that and worked on that. It seems like the world of psychedelics is really moving forward and beginning to be accepted in a way that it has never been accepted before. Is that something you see on your radar? Is that a positive thing or what's your take on that? Yeah. I think it's sometimes hard for me to see because when you work in psychedelics, you're in it all the time. You're always surrounded by it. I think when I noticed psychedelics were getting more popular was when my mom called me and told me she'd heard about it on the radio. And she was asking me, do you know about psilocybin? So that was a couple of years ago. And now I think my supervisor, Professor Hasler, he went to a medical conference recently in the United States. And he said every time block had a panel on psychedelics. And you could fill your entire conference with psychedelics if you wanted to. So it really does seem to be still taking off. And at the same time, we're seeing a type of research on adverse effects that we never saw before, which is good because, you know, thirty years ago, if you research adverse effects, you do it kind of with a background of drug prohibition. LSD is bad. Never take LSD. Don't do mushrooms. Here are all the bad things that can happen. There's just there was just not much nuance there. And then in maybe the earlier phase of psychedelic hype, people kind of thought we've had enough research on the bad stuff, let's focus on the good stuff. They were coming out of prohibition and trying to steer against this idea that psychedelics are dangerous and worthless. And now that psychedelics are a little more accepted, I think it's safe to research adverse effects in a way that's nuanced and in a way that isn't going to be, hopefully isn't going to be used to prohibit patient access for people who can really benefit from psychedelics. So I think that's why we're seeing so much good research into adverse effects now, nuanced research. Like on the scale, for example, we really ask people, not only have they had an adverse effect, but we ask them how it impacted them and how they feel about it. Like some people will have anxiety after a trip and they think it was ultimately a bad thing that they had trouble recovering from and it was awful and they would never do it again. And then some people have anxiety after a difficult trip and they think, well, ultimately, this was part of a healing process. And so that's why we included both of those things on the scale. And it's this kind of nuanced research that I'm really excited about and that I hope can really be informative as we try to figure out what the hell to do with psychedelics in the future. Yeah. Me too. There's so much there. And I think that there's so much hope and promise and there's definitely a dark side to it. But that brings up a question from another, someone listening. They say, what were the most significant challenges you faced during your research project? Oh, which research projects? All right. Maybe, I don't know. Maybe you can just speak about one that you found recently, like a recent project that you had some challenges on. Yeah. Let me think. Um, You know, the first thing that comes to mind has to do with trying to anticipate how your research is going to be used by people who are not you and who may not care what you think. And I think this is particularly I'm particularly conscious of this with adverse effects research. I recently wrote, it's not out yet, but I wrote a book chapter for an upcoming publication, an upcoming textbook basically that I would love to plug because it's, it's going to be really good. It's called psychedelic harm reduction published by Springer. I hope I'm allowed to talk about it, but me and a couple of colleagues wrote a book chapter or a chapter in that called traumatic psychedelic experiences, specifically talking about these kinds of like the worst of the worst of bad trips where people feel like they struggle to recover from it. Not that it can never be a good thing or be a catalyst for personal growth, but that it's hard and that the period after the trip is just very fraught for some people. And I was just constantly... neurotic about the possibility of being misunderstood you know because if somebody opens a book and they see traumatic psychedelic experiences that could easily give the impression that lsd is out there traumatizing people and you should stay away from it and particularly if people aren't motivated to read the rest of the chapter there's potential for misunderstanding um and at the same time you you still want to confront the topic with the seriousness that it deserves And so this tension between wanting to confront the dark side of psychedelics, but also not wanting your research to be used to prohibit psychedelics from people who could benefit from them. I think that's one of the biggest challenges that I've faced recently. Yeah, I can't wait to check out that book, and congratulations for that. I can totally see how it could be misinterpreted on some level, and it's interesting to think about. And it's a tension of empathy, just to add one more thing. I think there's a tension of empathy. On the one hand, you have empathy for people who have been through bad trips and are struggling and can't find resources. On the other hand, you have empathy for people who are struggling with depression and want access to psychedelics and who could really benefit from them in the right setting. And so those are both good motivations. And it can be hard to hold them in balance. Yeah, that's a great point. Do you feel there's a tension between the medical container and the recreational container or the optimization container? I think there's a tension if people who are a proponent of one are trying to control the other. I'm personally a fan of multiple contexts. Some people are not comfortable in the medical setting, whereas others feel more comfortable in the medical setting than anywhere else because they like having doctors around. I think ideally people would be able to choose between a myriad of safe settings. If everybody thought like me, there would be no tension. Kidding, just being facetious. But yeah, I think sometimes there can be tension maybe coming from both directions because the people who are, as you might say, recreational users feel misunderstood or maybe even oppressed by the medical system, perhaps rightly so. And then in the medical system, they're concerned about patient welfare and about some maybe shady underground practices that they've heard of or encountered people after. And so... I do sense some tension there, yeah. I don't have a solution. I don't think anybody does. I don't think anybody does, but it's interesting to get to see it. You hear these things like it's all medicinal. Maybe the recreational and situational is just a different form of medicinal on some levels. It makes me curious. if maybe proponents of both could acknowledge their own limitations, like proponents of the medical system should confront the fact that a lot of people don't feel comfortable in the medical system where they feel like it's failed them. And so that might be motivation for them to, to seek out something else. And then in the underground, you know, it's true that if somebody is in the underground and, and practicing in a way that's unethical, there aren't very many checks and balances on that. You know, what are you going to do if you have an underground therapist and you feel like they were abusive towards you or there's no board you can call to get their license taken away? What are you going to do? Call the cops. There's nothing you can do as a patient in that situation. So you're very unprotected. And I think that's something that the underground could and often does acknowledge that would maybe increase people's comfort with that. Yeah. Sometimes I'm hopeful to see the future of psychedelics embrace the most subjective behaviors. I think that there's so much in there. When you look at a test and you're trying to figure out, did this really help this person? Maybe asking the wife, is your husband less of an asshole? Or the tears of a mother? You know what I mean? It's over there, right? That's valuable information, right? Absolutely. That's something that some of the early Hopkins research did this. They asked like community writers or family members to evaluate whether people's depression symptoms were better. But yeah, yeah, this is, it's a great idea. Yeah. And it's, I don't know. It's, it's valuable to me. I think that, And in some ways, I guess the reason I brought it up is it seems that science is beginning to sort of bring some of that information in and find a way, even with like the HRS in some ways, like you're finding a way to quantify the subjective, which has been lacking for a long time. And I think it creates more of a whole picture, right? Yeah. And I also think we need a combination between things like questionnaires, but also just interviews, like just let people talk and tell about their experiences. Maybe you can't do as many statistics on that, but people can still read it and it's part of the whole picture. Yeah. Do you think it might be possible in the future to like, maybe there's a way to like introduce linguistic analysis into those interviews. Cause like, does a person start changing their language differently under a different dose? Do they start using different metaphors or do more flowery rhetoric or do they just get to the point where they can't even create a word? Like, what does that mean when you can't even talk? I have a colleague who does this, actually, with trip reports that he gets from, yeah, from Arrowwood. You know Arrowwood, right? Yeah, of course. He extracts trip reports from Arrowwood, and his name is Adrian Hase, H-A-S-E. I can send you a link to his school papers. Please do. He did this. He did semantic analysis for... And there was one paper that was published a while ago. I forget what the topic was, which makes me a very bad colleague. But recently he did one on like adverse effects as well. So how people talk about different adverse effects and surprised people who took ayahuasca talk about vomiting a lot more than everybody else. But he did it using an R script before chat GPT, like before these language models. And now people are using language models like chat GPT for that. I haven't done it, but it seems super promising because it really reduces the amount of time it takes to do one of these analyses. And it's pretty good. Yeah, I would imagine it is. Another interesting thing I've been thinking about for a while is, is there a way to figure out the difference between cultural and biological? Some of these things that happen in a trip, these deep trips, how do we know what is cultural and what is biological? It seems like a pretty fascinating idea, right? Mm-hmm. Oof, yeah. Well, I think you'd have to just take, to do it in different cultures. Right, right. Yeah, like take some people in the United States and some people in, I don't know, give me a country. Brazil. Or Brazil, yeah. Costa Rica. Yeah, but it would be really hard because you'd have to keep some other things constant. I mean, you'd have to decide what you wanna keep constant. In different cultures, you're probably gonna have different preparations for the psychedelic experience. So that's gonna influence people. And one kind of funny thing that you see in some of the data is that if you compare Switzerland and the United States, both of them have done a lot of psychedelic studies, But in general, the people in the United States seem to have more complete mystical experiences than the people in Switzerland do. Like Americans are more mystical or something like that. And part of that could be cultural. It's not quite clear. Part of it could also be that in some of these studies, people were prepared for the experience in a bit more of a spiritual way. Whereas in Switzerland, we kind of don't, we don't automatically prepare people for the experience in a spiritual way. You know, if they are a spiritual person and bring that in, then we meet them where they are, but the protocol doesn't have that in it. Whereas I think in, for example, some of the early Johns Hopkins psilocybin studies, they were. specifically looking for mystical experiences. And so they had everything set up to kind of facilitate one. But that might be an interesting cultural difference that you could hypothesize that Americans are a bit more religious on the whole, and maybe a bit more spiritual for better or for worse, and that that's why they tend to have more mystical experiences. But I think you definitely see cultural differences there. Abigail, why LSD? Like, what is it about LSD? OK, so there were a lot of reasons. Some were practical, some less so. So one of the reasons was LSD is longer, which, I mean, that also has a disadvantage because you have to be in the lab for longer. But it means that you have two relatively long phases of the experience that you can use for study. In the first phase, like the first four to six hours, there's the peak, the strongest part of the experience. And then after that, there's another six hours or so in which people are still on LSD, but they're not tripping so hard. And with psilocybin, the whole timeline is a lot shorter. And so for our study, we had a lot of experiments we wanted to do, and they weren't necessarily things that we wanted to have people do while they were peaking on LSD. So we thought LSD will be nice because people can have their trip and we don't bother them too much during the trip. Like once an hour, we ask them some questions. But for the peak of the experience, we try not to bother them too much. We're just there for support. They can talk to us or not. They can interact with us or not. They can tell us what's happening or not. And then after they start to come down, that's when we do experiments. And we have six hours or so. Well, we use about four of them. We have four hours in which we can do experiments while the person is still on LSD, but also very much capable of doing the experiments without discomfort. So that was one reason. It's just the long timeline. And then another reason is LSD is actually cheaper. Like by a lot as it stands now. I hope that changes. And I think there was also a bit of a cultural reason too. You know, LSD was discovered in Switzerland. It's kind of, it's a Swiss product. And Switzerland does a lot more LSD research than the United States compared to, for example, psilocybin. The US does more psilocybin. or at least did. And I think part of that has to do with the cultural stigma around LSD that arose pretty strongly in the United States, but a lot less so in Switzerland. Yeah, I could totally see those points. It's such a fascinating compound to think that for like eight hours, you're transported into this alternative state where things look different, they sound different, they feel different. It's incredible. Yeah. Audrey says Audrey back. Thanks. First off, Audrey, thank you so much for being here. I'm super stoked you're here and talking to us. And she says, Are there differences in the data between trips and clinical settings and other or are there not enough respondents from clinical settings? Yeah, I mean, there certainly are. It's kind of difficult to compare them both in a study because the whole setting is so different. that it really impacts the experience. But you can see, for example, in the clinical settings, I think because people are tripping under supervision, for better or for worse, you tend to see fewer adverse effects, although you still don't see that many outside of uh clinical settings um you also especially compared to ceremonial settings like retreats I think sometimes people who do it in clinical settings go a little bit less deeply into the experience particularly if there's experiments going on that are kind of distracting them or pulling them out of their trip for a second. So that's something and yeah, I mean, everything about the setting is different. And that's going to strongly impact the experience, even if I can't think of a paper that directly statistically compared those two settings, you can see in the different studies in recreational settings versus clinical that there are probably some differences. Yeah. Probably the biggest difference I would say is the variability of the experience. Like in a clinical setting, everything's pretty much the same for everybody. And between clinical settings, you have some basic structure that tends to be the same. Like people have a certain amount of preparation, they're supervised during the experience. And then ideally they also meet with the researchers at least once, if not twice after the experience. And they're in a room inside the whole time, typically. Whereas in recreational settings, you have a lot more variability. You know, you can have a trip sitter or not. You can be outside or inside. You can be comfortable in the setting or not. People in clinical studies also screen the participants a lot because you don't want to be responsible for somebody having really strong negative effects. And so in recreational settings, you don't have that either. So there's just way more variability outside of the clinical settings. You know, it, I don't know, but I've read a few reports on potentially psychedelics being something that could trigger schizophrenia in people that may have it in their genetic code or something like that. Do we know anything about that? Is that possible, or is that just sort of speculation? It's unclear, and it's something that researchers are still figuring out. I recently saw a paper suggesting that psychedelics might raise the risk of somebody who's predisposed to a manic episode, but not necessarily to schizophrenia or to a psychotic disorder. But schizophrenia and mania share a lot of genetic risk. There's a big overlap. And so it's not entirely clear. The risk seems to be pretty small. but it may very well be there. And personally, if I had schizophrenia in my immediate family or mania, I probably would not roll the dice. Yeah. It's interesting to me. I feel like some of the people that may have the most serious sort of conditions may benefit from psychedelics the most, but it's such a dice throw. It's such a gamble that people don't really want to try. I don't understand it, but I hope we get to the point where maybe we figure this stuff out. Yeah. And I mean, there's huge variability, too. I've seen case reports of people who had schizophrenia who felt like psychedelics helped them. Maybe they help. I mean, you can have schizophrenia and have different symptoms from somebody else who also has schizophrenia. So maybe maybe there's some potential for it to help with certain symptoms and not others. And then there's people for whom LSD would trigger a psychotic episode. And there's just this huge variability and risk. And I think risk is a huge topic with psychedelic substances. It's never zero risk and people should be empowered to decide the risk for themselves. In a clinical trial, we give people the information and we say, is this a risk you wanna take upon yourself with our support? And then they say yes or no. But in recreational settings, like with people who don't have a structured setting where they're being presented with the risks forcibly before they're allowed to have the substance, Sometimes people don't have such an opportunity to make an informed choice. And I hope that can change. I hope that we can have better information out there easily accessible for people who are trying to decide whether they want to go to a psilocybin retreat or an ayahuasca retreat or whatever safe framework for psychedelics they choose. That's a great point. It's a great point. I was speaking with someone. I'm super fortunate to get to talk to so many cool people, yourself included, and someone I was talking to the other day, and I've heard this before, is that when they talk about the difference between LSD and psilocybin, a lot of people will say that psilocybin is embodied. They feel like they can talk to a presence there on some level, and LSD seems to be more cerebral. I'm curious to get your thoughts on that. Do you ever have those feelings, or do you talk to people that have those same sort of ideas, or what's your thoughts on that? I've heard it both ways. Like I've heard some people say LSD is more energizing and psilocybin is more sedating. And I've also heard other people say the opposite. Right. I've heard some people say that psilocybin always goes right to the point, whereas LSD takes a while to get there. And then I've heard from another person, the exact opposite characterization. So I don't know what's going on there, man. I think some of it, it would be really hard to disentangle the actual differences in pharmacology from just differences in people's expectations. Like for example, if you are taking, if you're eating a mushroom that might feel different and have different associations than if you take the little alcoholic glass of LSD that we have in the lab. So it's hard to disentangle. I completely believe that they might have different subjective effects for different people. I think probably some people could tell the difference, but what exactly makes up that difference might be different from person to person. Yeah, it's so fascinating to get to see some of the similarities and difference between this wave and like the last wave. And I was born in seventy five, so I wasn't around for that last wave. But it seems to me that when I start reading about like Leary or Ram Dass or you know, even Ted Kaczynski for some level, like it seems that the last sort of psychedelic revolution was from like the ground up. And it seems on this level, it's more Huxley like, and that the people at the top are starting to find a way. It's like, Hey, this could be very useful. Do you have any, any thoughts on, on the revolution or the idea of psychedelics being a bottom up or a top down sort of a. I think this one's from the ground up too, because what might look like top down is maybe really ground up. There was a study recently that showed that a lot of people who work in the field of psychedelics also consume psychedelics before they started to work in the field of psychedelics. So it's not everybody, but it's quite common. And I think you have a lot of people in the field who are motivated kind of from the ground up. to try and bring something into society that they feel is useful that they feel has been neglected. And so in that way, I think it is from the ground up, but there probably are some differences, right? Like, can you think of any other, do you see any other stark differences between last time and this time? Well, I don't see any Dayglo school buses driving around. I don't see Tom Whoop. I don't see any electric Kool-Aid acid test happening. Maybe we're in the late fifties still, you know, I, I don't see why not. Like we have electric school buses. Like those should be painted and be rolling out full screen right now. Like what better time? Hey, be the change you want to see in the world. I know. Yeah, but that's true. It does seem a bit more, at least at this point, it seems relatively sober. If not medicalized, then people are nervous that it could be taken away again and maybe have learned some lesson from the past, I hope. Yeah. Sometimes I wonder, is it taken away or does it just subside? Sometimes I think like, yeah, man, we should have put it in the water. This is a horrible, people are going to get blasted for this. I'll probably get blasted for this. But sometimes I think like, yeah, we should put it in the water. That would totally. totally work like just a little bit, you know, but then you go, well, there are a lot of people that probably think about the wrong way. It's a nonspecific amplifier, probably not a good idea, but you know, I wonder sometimes if this, these waves of psychedelics, they find their way out into the open. They, they, they inspire the people that are supposed to find them and then it subsides back and the change happens and it comes in cycles. Do you think it's more of a cyclical thing or what's your thought? That's a really good question. I think, you know, when people are afraid of it being, taken away again, what they would want would be the FDA stops funding studies and there's no path to legal use for people. Right now there is a potential path to legal use for people someday if we keep our act together and the trials continue to show good results. And if we continue to care about safety, but you know, you may have a point. Sometimes I wonder, is it sometimes a good thing that psychedelics are hard to access? Because the psychedelic experience requires something of you that's not so easy. And maybe you don't want people falling into that on accident. Maybe in some ways it's a good thing if it's hard to access, if there are some barriers in the way. I don't know what those should be or how strict they should be. But maybe it's not such a bad thing. That's a great point. Maybe, I mean, you should have to do some work, right? Like you should have to do some analysis and some safety concerns and do a lot of hard thinking about like, is this the right time to do this right now? Or am I in the right spot for this? Like maybe all those questions should be answered by you before you actually get access to them on some level. yeah because it would ensure that you have a good enough reason that you're willing to jump through a few hoops to get to the psychedelics because I mean during the psychedelic experience it's possible that it might just be amazing and wonderful from the beginning to end but it's also possible that you might be some confronted with some really difficult things And in order to confront difficult things, you need to have a reason to put yourself through that if you're going to be successful. And if you don't have that reason, you're just going to think, oh, I don't want this. I want this to stop. And that's a bad trip. It's a potentially traumatic experience. And so having some kind of barrier to access might ensure that people who come to psychedelics have enough of a reason they wanted to do it that they'll go through the challenge and they'll stand up to the challenge if need be. Yeah. Here's, here's another difference that I, that when we look back at the past versus today is that where's the anti-war movement, you know, that seems there's like been a commodification of veterans on some level. And I don't have all the facts in front of me, but you know, a lot of people are like, look, we've got to help out these veterans with PTSD. And it seems to me, if you really were going to help them out, that you would have an anti-war campaign instead of like, yeah, just come over here when you're done and we'll treat the symptoms. You know, it's kind of an interesting process, right? Yeah, it is. And I wonder if it has a bit to do with the fact that, at least in the US, we're not as explicitly in a war as we were in the Vietnam War, for example. Yeah. I mean, there was the Iraq war and we're kind of still there, but to be honest, just thinking about it, I mean, I have the excuse of not even living in the United States, but I don't actually even know what we're doing over there anymore. Like, is it even still officially a war? So there's, I mean, there's gotta be fighting, but I think maybe part of it has to do with, with that, with the fact that it doesn't feel as much like we're in a war, but you know, there's still these traumatized veterans. So what you said makes absolute sense. Why not prevention? Yeah, I think on some level it might stop the funding. I think that the VA gets, they're like, hey, just take it easy. We don't need to talk about the whole war thing. Let's just help out the people over here. I don't know, but it's definitely a difference. Brad comes in here. Brad says, perhaps best to keep it accessible for personal growth and not for recreational use. I don't know if you can separate those two things, Brad. What do you think? Good question. I mean, personal growth would mean, I guess you'd take it with a certain type of intention. Recreational use, the term recreational is tough because I think people use it to mean a lot of different things. Like sometimes people use it to mean anything that's not in a clinical setting. And sometimes people use it to mean fun and not much more than fun. Just based on the comment, I think here it's meant a bit more like fun and not much more than fun. Yeah, I don't know. I think there's also what's also a question here is what should be a legal decision that the government makes and what should be a personal decision? And also, what do you believe is the government's responsibility? Is it the government's responsibility to protect people from themselves? Because if so, if you believe that, you'll probably tend to support more drug laws. Whereas if you believe that that's not the government's responsibility, then you would tend to support decriminalization and things like that. And people can make the personal choice to take a substance or not. And it may be a terrible idea, but that doesn't mean it's illegal. Lots of really bad ideas are illegal, right? Right. It's fascinating. Abigail, what's going on at Mines and Alps? Like you have all these branches that you're branching out into all kinds of stuff now. What are you most excited about on these new things that you're doing? Yes, I'm not at the mind foundation anymore. But I am. So I'm the research coordinator at the Alps Foundation in Switzerland, which is an amazing group of people. So the Alps Foundation was founded, I think, five years ago, something like that, four or five years ago. And its main activity is we do a conference every year in Switzerland, the Alps conference. We've actually managed to do it every year, which is shocking, but we still do it every year. And it's just a little Swiss conference on psychedelic science. It's pretty small, intimate. It's like a few hundred people. And then we have like fifteen speakers or something a year. And we post all the talks on YouTube if you want to see some of them. But we do the conference every year. And so It's a cool opportunity to invite scientists from all over. Just who do we want to hear give a talk? And so that's something that's always going on. And then we also have our own research projects. So we've got two research projects that are very much ongoing and two that we're just now starting. And the main one I'm responsible for has to do with the impact of set and setting in psychedelic experiences. So that connects to a lot of what we talked about today. And we also are, of course, using the hallucinogen rating scale in that project. So, yeah, we basically did this huge, well, pretty big study where we recruited a thousand people to answer a bunch of questions about related to like set and setting of the trip that they had taken. So we were looking for people who had tripped kind of recently in the past year. And we had one hundred questions about where what kind of environment they were in, who they were with, of course, what drug they took. Things like, were you in nature or not? Were you listening to music or not? Had you been meditating recently, etc. ? all these like set and setting things that people think are important. We asked people about all of them and we actually just finished collecting the data for that study. So we got our one thousand people and now we're starting to analyze it. And yeah, I have no idea what's going to come out of it, but it will be really interesting to see which set and setting factors are the most important under what circumstances. So that'll be exciting. Yeah, it'll be totally exciting. I'm excited for you, Abigail. I feel like you're just getting warmed up. Like you've accomplished quite a bit already. I know you got so much more on the books. I feel like you're getting warmed up and I can't wait to see all the cool things that you come up with next. And as we're coming up on the hour right here, I was hopeful that you would be so kind enough to tell people where they can find you, what else you have coming up and what you're excited about. Yeah, absolutely. So I don't really have social media. I do have a LinkedIn. Yeah, it's just my name. But if you want to see our research, we have a website called molecularpsychiatry.ch. It's our laboratory website. And all of our research is listed there, including ongoing studies. And some of those studies are online. So anybody who has had psychedelic experiences can participate in those and help us out. And sorry, what was your other question, George? What are you most excited about for moving forward? Yeah, well, this year I'm going to finish my PhD. So that's exciting. Next time I'm here, you have to call me Dr. Abby, okay? Yes. But yeah, so we are finishing, nearly finished with the study on the effects of LSD on neuroplasticity in healthy subjects. And as I mentioned, I just started to analyze the data. So now I get to see what these years of effort are going to show us. And yeah, that's really exciting, really exciting. Yeah. And how long is that process going to be, do you think? Oh, well, I have to defend my dissertation end of the year. So until then, there's a deadline, you know? Right. If I don't do that, I am screwed. So this year, that would be something to report. You're going to crush it. You're going to crush it. I can't wait to – when it finally is published, I can't wait to read it and have you back. And like I said, I'm super stoked. And for everybody within the sound of my voice, I hope you go down to the show notes and check out all the work they're doing over there at Freiburg. Look at some of the published papers that Abigail has put out, some of her colleagues have put out. They're doing really cool stuff over there. And Abigail, I'm super stoked for you. And hang on briefly afterwards. But to everybody within the sound of my voice, I hope you have a beautiful day. Hope the sun is shining on you and you have the courage to chase your dreams down. That's all we got, ladies and gentlemen. Aloha. Thank you so much, George.

Creators and Guests